After having recently completed the SANS training course ICS/SCADA Security Essentials in Washington DC during a balmy week in June, I came away noticing that other participating students had a bit of confusion around the subject of a DMZ for industrial networks – or more specifically – for IT/OT network integration.

Part of the reason for the confusion could be that for nearly three decades, digital network DMZs or “demilitarized zones” have been used as a data protection strategy in IT networks to broker access to information by external untrusted networks. This IT DMZ model and approach is well established, but is not necessarily an effective security measure when applied to OT networks. We’ll get to why that is a bit later.

DMZs are in essence a network between networks, and in the industrial security context, an added network layer between the OT, ICS, or SCADA, network and the less-trusted IT or enterprise network. In theory, when correctly implemented, no TCP or any other connection exchanging messages should ever traverse a DMZ between IT and OT; it is a place where information originates from, or terminates completely.

For industrial purposes, what should go “inside” the DMZ is all of the applications and servers that have TCP connections out to the IT network. In practice, this can be a whole range of things; so when designing IT/OT network integration architectures, we at Waterfall generally see customers deploy an intermediate system to aggregate OT data which needs to be shared with the enterprise. The most common aggregator is one of the many process historians, or one of the many variants of OPC server.

IT/OT DMZ Security

The modern industrial DMZ acts as a zone and conduit system protecting physical processes, separating networks according to their different purposes, requirements and risks. What we learn at reputable training such as SANS, is that in theory the best practice for implementing an IT/OT DMZ is to put two firewalls around the DMZ as is depicted the IT DMZ model: one between the OT network and DMZ network, the other between the DMZ and the IT network. This practice supports the assumption that two firewalls reduces the likelihood that single firewall software vulnerability will open an attack pathway straight in to control system networks. In addition, all three networks must be on separate domains with their own authentication systems and no sharing of domain credentials. This last point was highlighted at the US ICSJWG Fall 2019 meeting.

In practice, we often see something much different. Most sites deploy only a single firewall with three ports – one connected to IT, one connected to OT and one to the DMZ network – meaning single vulnerabilities are again a concern. More fundamentally, modern attacks don’t exploit software vulnerabilities, modern attacks exploit permissions. From an attack perspective, exploiting vulnerabilities involves a lot of work and code writing – unless of course someone else has already done the work and released an attack tool to the public. Exploiting permissions, on the other hand, can be as easy as stealing the firewall password, or stealing a password on the IT network that the OT network then trusts or allows an attacker to go into a historian or other system in the DMZ right through the firewall.

Going to two firewalls does not help this situation much. For example, with the multitude of updates, patches and rule writing, two firewalls can make supporting the DMZ more difficult than attacking it.

Modern IT/OT DMZ Design

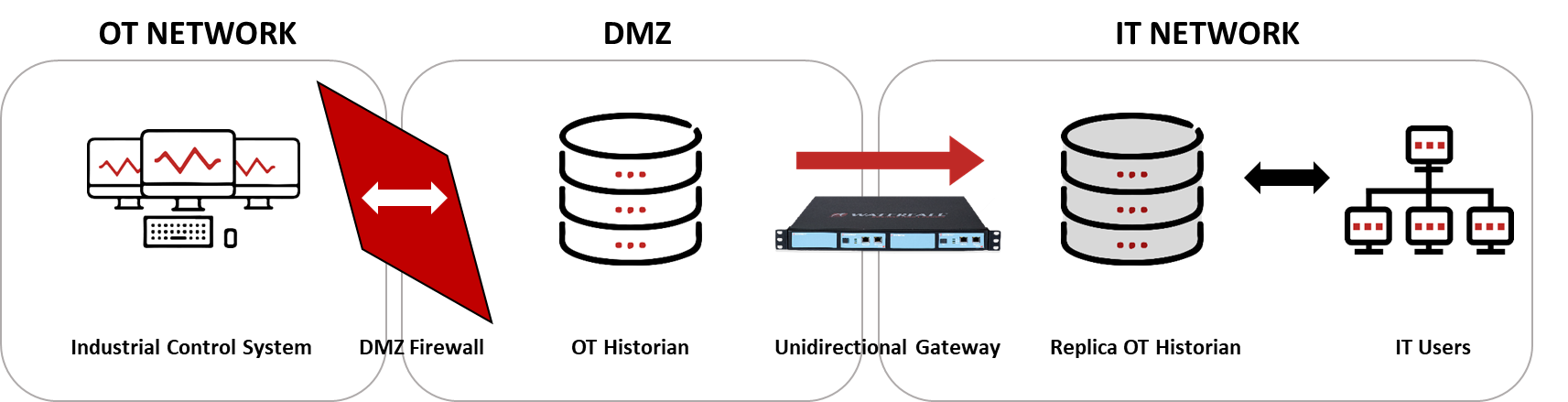

Modern advice describes and recommends that one side of the IT/OT DMZ be protected with unidirectional gateways to replicate OT systems to the IT network. The defining feature of a unidirectional gateway is that it is hardware-enforced: a combination of hardware and software that physically moves information in one direction only – meaning no messages whatsoever (including attacks) can enter the protected OT network from external sources, thus fulfilling the mission and purpose of implementing an IT/OT DMZ. The software element of unidirectional gateways replicates industrial servers and applications in two common scenarios with a Modern IT/OT DMZ:

- either replicating a historian or OPC server insider the OT network with a unidirectional gateway to the DMZ network whereby the IT network accesses the replicated server inside the DMZ through a firewall,

Figure 1: Modern IT/OT DMZ Scenario 1

- or, replicating the historian or OPC server which sits inside the DMZ with a unidirectional gateway to a replica server sitting on the IT network for corporate use. In both scenarios, the IT replica of the DMZ OPC or historian server is still the focus for IT/OT data exchange – it is now thoroughly protected in its original operational state.

Figure 2: Modern IT/OT DMZ Scenario 2

Safe IT/OT Integration

To sum it up, the core purpose of the IT/OT DMZ is two-fold: security and integration. In the industrial context, a DMZ must prevent arbitrary connections to act as attack channels from the internet straight into OT systems, not be an added layer of complexity for the security of control systems nor a funnel through which an attacker can access ICS. This is what the unidirectional technology in the DMZ accomplishes: elimination of inbound attack paths through hardware-enforced security. If one is not already in place, a historian or OPC server may need to be deployed as a focus for integrating the two networks. In order to not only thoroughly secure a DMZ with industrial-grade protections but also simplify the setup and maintenance of the DMZ is with unidirectional gateways either on the OT or the IT side and a firewall on the other. Double layers of firewalls are inherently insufficient – modern industrial security advice positions a unidirectional gateway at either the “top” or “bottom” of the plant DMZ as a way to enable safe IT/OT integration.

She has over 10 years of experience as a strategic consultant for tier 1 global consulting firms across multiple industries in four countries.

- The 2023 Threat Report – At a Glance - June 15, 2023

- OT Risk Management: Getting Started and Assigning Risk - May 3, 2023

- 4-Step Approach for Choosing an OT Security Vendor - March 11, 2023

English

English Français

Français Español

Español עברית

עברית Deutsch

Deutsch 日本語

日本語 한국어

한국어 中文

中文 اَلْعَرَبِيَّةُ

اَلْعَرَبِيَّةُ